An already cult armour, yet superbly revisited. Sandy, minimalist imagery embellished with first-class effects and dazzling explosions. A surprising alliance between a taciturn bounty hunter and an endearing orphan (The Child). The buzzing Star Wars show The Mandalorian, launched just over a year ago, already enjoys its own identity and mythology, both connected to and separate from that of its parent franchise.

Following the release of Season 2 in early November on Disney+, streaming guide and aggregator Reelgood reported a “watch” market share of 5.7% for the opening weekend; the third-highest rate ever recorded (only Amazon’s The Boys Season 2 and Netflix’s Stranger Things Season 3 performed better). Over and above its audience and cultural success, The Mandalorian is a captivating subject for analysis, perfectly embodying the novel narrative and distribution models gradually being adopted by the world’s biggest media franchises. Let’s explore.

- Read below ➔ Star Wars Part I: How ’multi-epic’ storytelling is saving the galaxy

- Read also ➔ Star Wars Part II: How ‘multi-epic’ storytelling is reshaping franchise distribution

From a blockbuster-based to a blockbuster-driven franchise: Star Wars’ transmedia DNA

Saying that Star Wars is one of the most powerful cultural forces worldwide is a laughable understatement.

Back in 1977, the first installment New Hope smashed all ratings records, selling more than 170m tickets across the US and taking a then-record-breaking USD 460m at the domestic box office. Adjusting for inflation, A New Hope is still the second-highest grossing film of all time. Creator/director George Lucas — with cautious support from Fox — developed and marketed this imaginary universe against all trends and odds. From both an artistic and commercial perspective, it literally established a new, revolutionary playbook.

Since then, the franchise has flourished. In 2012, Disney acquired the production company/IP owner Lucasfilm for USD 4b. Under the Mouse’s sovereignty, the 5 subsequently-released blockbusters The Force Awakens (2015), Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016), The Last Jedi (2017), Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018), and The Rise of Skywalker (2019) cumulatively generated an impressive USD 5.7b in gross box office revenues.

But the space opera goes well beyond movies. A true pioneer, Lucas built Star Wars as an IP from the ground up. Way before A New Hope became a success. Even before it was an end product. Instead of pushing for a more advantageous contract with Fox, he instead focused on securing the ownership of Star Wars’ licensing rights, as well as a pre-agreement for sequels. A winning strategy, as it turned out — the first title’s cult status fuelled a lucrative IP machine. Star Wars became clothes, novels, toys, comics, a television special (Star Wars Holiday Special), and much more. This was so fruitful that Lucas was able to produce the second opus The Empire Strikes Back independently, relying on Fox for distribution only.

With “multiplatform” storytelling, the process of licensing IP is not solely perceived as a revenue-generating activity, but rather contributes to building new entry points and sub-stories within a fictional world.

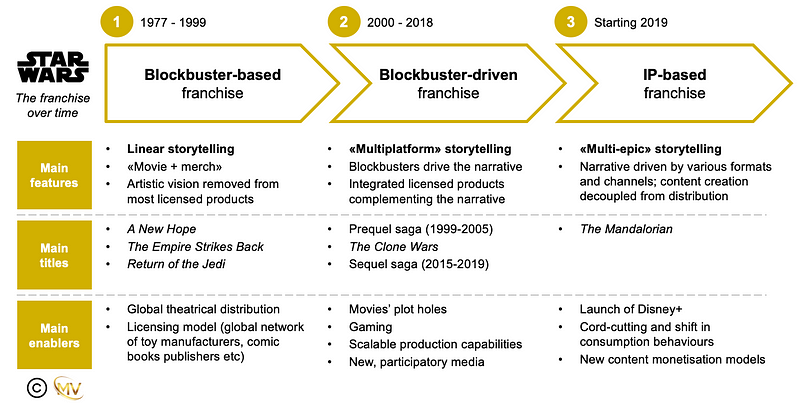

Alongside the initial trilogy (from 1977’s A New Hope to 1983’s Return of the Jedi), Lucasfilm primarily explored the commercial potential of its media franchise through a “more of the same” approach. Star Wars’ rights were mostly sold to toy manufacturers and other licensees for logoed products, both enhancing IP awareness and enabling the more hardcore audience members to express their fandom through a plethora of licensed items. Almost every licensed product directly referenced a movie-related scene or, in particular, a specific character. This is what I call a blockbuster-based franchise model.

In 1999, Lucasfilm heralded in a new era for its treasured galaxy with the launch of The Phantom Menace; a USD 115m budget blockbuster initiating the so-called prequel trilogy, which explores the origin of Star Wars’ most enthralling character, Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader. In the same year, The Matrix hit movie theaters worldwide. In their own pioneering ways, both franchises pushed the entertainment industry’s storytelling and commercial standards to a whole new level.

With the advent of novel participatory media as an enabler, both Star Wars and Matrix experienced what Henry Jenkins calls “multiplatform” storytelling in the book Convergence Culture. According to this view, the process of licensing and merchandising IP is not solely perceived as a revenue-generating activity, but rather contributes to building new entry points and complementary sub-stories within the fictional world. All this is aimed at nurturing a broader storytelling system.

Indeed, The Matrix’s creators (the Wachowski brothers) strived to incorporate an artistic value-add into most of their merchandising/licensing initiatives. For instance, the video game Enter The Matrix (2003) was not leveraged as a pure movie replicate, but rather as a way to address the movie’s plot holes and extend the encyclopaedic richness of its universe. With regard to Star Wars, the most notable “multiplatform” experiment is definitely The Clone Wars; a 7-season animated series that, story-wise, bridges the events of Attack of The Clones (2002) and Revenge of the Sith (2005). Not only the main characters are explored in more depth, but new ones are introduced too. The Clone Wars stretches the galaxy with deep brand consistency, leveraging many assets from the main movies (e.g. actors’ voices, flagship sounds, planet names, spaceship designs). The last four episodes, which feature multiple references and narrative synergies with Revenge of the Sith, have an impressive average IMDB rating of 9.9.

In this case, the main movies are only the engine behind a broader, transmedia storytelling machine, which is what I call a blockbuster-driven franchise model.

While “multiplatform” storytelling presents a lot of challenges (e.g. coordinating collaborative authorship, co-creating with both licensors and fans in a coherent way, durably sustaining an ecosystem of standalone stories that serve an overarching narrative arc, etc), its fundamentals materialise everything that a modern entertainment franchise seeks to achieve.

But while Star Wars has clearly been “multiplatform” storytelling’s visionary pioneer, it is not perceived as the game master anymore.

Marvel thrives as a native “multiplatform” universe; Star Wars fears franchise fatigue

Star Wars’ modern paradox is pretty straightforward. While the franchise still represents an undisputed pop culture phenomenon with large, global fan communities generating immense studio and licensing revenues, its critical/public appraisal metrics are dangerously declining. The Rise of Skywalker and The Last Jedi (the last two titles of the sequel saga) only scored an average audience rating of 64% on Rotten Tomatoes, suffering from both intrinsic flaws (notably the disconnected vision between the two directors, Rian Johnson and J.J. Abrams) and a fundamentally divided fanbase. As a 43-year-old franchise, Star Wars is struggling to find a consensual artistic position across old trilogy, prequel trilogy, and sequel trilogy fans.

Adding to harsh (sequel) movie reviews, there is regular fan backlash against Disney’s ownership which, shortly after acquiring Lucasfilm, declared most fan-generated and extended universe artwork and stories “non-canon” (not integrated into nor considered into as the official, Disney-led storyline). Undeniably, the Star Wars franchise is strongly affected by the burden of its own legacy.

Unlike Star Wars, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) adopted “multiplatform” storytelling in a native rather than sprawling way.

Conversely, its sister epic — the Disney-owned franchise Marvel franchise — is thriving. The last The Avengers movie End Game generated three times more revenues than Rise of Skywalker, alongside a 90% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes. Each franchise has its own proprietary culture, artistic tone, and set of heroes. But the main differentiating factor between them lies in the former’s unique capabilities system towards world-building.

Unlike Star Wars, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) adopted “multiplatform” storytelling in a native rather than sprawling way. When Iron Man was released in 2006, Marvel Studio was already carefully planning ahead, using a phased structure to smartly articulate multiple movie-based stories around a consistent, overall arc. Each production uniquely balances consistency (Marvel as the core IP) and diversity (each superhero as its own brand), which keeps building momentum until The Avengers movies celebrate the entire universe in an epic way. MCU’s “multiplatform” formula, mastered by industry leader Kevin Feige, is working like a charm. And it has far from fully exploited the potential of alternative content formats. The franchise, very much movie-driven, will see a new big-budget show being launched on Disney+ by the end of the year (WandaVision).

Although Star Wars leaders have full transparent access to MCU’s creative strategy and operating model through their shared mother company Disney, it needs to be acknowledged that Lucasfilm faces many more contextual barriers than Marvel does (mainly the following):

- Heterogeneous and multigenerational fanbase

- Disappointing critic reviews (last movies)

- Struggle to integrate fan-generated content

- Low level of acceptance of (most recent) leading characters/main heroes

- Still searching for the right “multiplatform” formula (Disney’s initial plan to deliver a new film every year was stopped after the commercial and critical failure of Solo)

To reiterate Henry Jenkins’ expert view, a media franchise needs to act as both a cultural attractor and a cultural activator. A cultural attractor is what brings fan communities together (basically stimulating fan interest), whereas a cultural activator is what drives people to walk the extra mile and commit, play, share, create, talk, and so forth. Star Wars’ latest blockbuster movies still managed to attract fans, but barely activated them. And this is precisely the point. Even if it can count on a broad, deep, self-sufficient fan ecosystem, a franchise without activators is just a dying one.

So Lucasfilm and Disney continue pushing towards integrated storytelling, combining traditional (e.g. the forthcoming launch of the new book and comic series The High Republic) and modern mediums (e.g. VR experience Tales from the Galaxy’s Edge, launch of the video game Squadrons to tap into the esports hype). This is good. But if a franchise is unable to renew its fanbase/combat fatigue through flagship products with a large cultural impact, it will ultimately disappear (e.g. The Matrix).

The rise of The Mandalorian: turning “multiplatform” into “multi-epic”

Given its colossal investment, it was obvious that Disney was going to react before the fate of the franchise was sealed. In order to give back to Star Wars its long-awaited impetus, fans had to wait until November 2019 and two fully integrated events: the launch of the streaming platform Disney+ and the first season of the original The Mandalorian.

The Mandalorian was a risky bet by Disney. With an eye-watering budget of around USD 15m per episode, the first season is one of the most expensive shows ever produced, accounting for approximately half of a Star Wars blockbuster movie budget. What’s more, the series is a digital original (no pay-per-view monetisation nor theatrical release) purely exploited through merchandising and Disney+. It was a smart bet though. Not only did “Mando” win over the public (both fans and non-fans), but critics also. Earlier this year, director Jon Favreau walked away from the Creative Arts Emmy ceremony with 7 awards (notably Special Visual Effects — a legacy of the impressive setting technology StageCraft). Unanimous critical and public approval is an unequivocable indicator of renewal for a franchise long decried artistically.

These factors directly propelled the Star Wars franchise into its third era, enabling epic/premium content to be produced, distributed, consumed, and monetised in a pluralistic way.

From a broader perspective, it really seems that The Mandalorian was the missing link for Lucasfilm to fully transit from the second (blockbuster-driven) to the third (IP-based) Star Wars era. Overall, The Mandalorian’s key game-changing attributes can be summarised as follows:

- Its editorial tone (an assumed style not hugely concerned with satisfying every single fan segment — which is, in the case of Star Was, not realistic)

- Its revolutionary format (not for a TV show, but for a blockbuster-type production)

- Its potential to integrate various references from and drive narrative synergies to other Star Wars titles

- Its distribution/monetisation model (OTT/direct-to-consumers)

These factors directly propelled the Star Wars franchise into its third era, enabling epic/premium content (“cultural activators”) to be produced, distributed, consumed, and monetised in a pluralistic way. Indeed, if two seasons of The Mandalorian cost as much as one movie/blockbuster to produce, it implies that the respective ROI is expected to be equally high. This fundamentally means that production can now be decoupled from commercials, opening up a broad new range of format/channel/monetisation combinations to be calibrated on a content-by-content basis.

It is obviously relevant to all major media franchises. It is all the more relevant for Star Wars, whose diverse fan communities need to be activated in a highly tailored way. Indeed, we can assume that, going forward, theatre-launched blockbusters would serve segment X, The Mandalorian segment Y, the next Disney+ Star Wars show segment Z, etc. More than just covering the fanbase as a whole, the individual productions would reinforce each other and, like MCU, deliver unifying titles at the highest epic level to close or open related narrative arcs.

As movies increasingly become one type of activator among many, “multiplatform” storytelling (blockbuster-driven narrative) is now turning into “multi-epic” storytelling (IP-based narrative). Ultimately, IP is taking over the role of blockbusters as the franchise’s main driver, orchestrating the narrative arcs and organising the overall storyline regardless of format or commercial model — which, as stated above, are not blockbuster-centric any more. This is simply the starting point of the new Star Wars era.

Reflecting the craze for Season 1, S02E03 of The Mandalorian has garnered praise, notably by featuring a major figure from The Clone Wars. “Watch Clone Wars to make this episode 100x better,” commented one fan on Instagram. The entry points are multiple; references can either go unnoticed or come as a shock depending on the viewer’s level of knowledge. While the nature of the experience varies from one audience segment to another, the common denominator remains the enhanced franchise attachment of each of them. At their very own level. How do you like your epic?

Star Wars’ franchise model over time: